HISTORY OF KOI

Dr Ronnie Watt and Servaas de Kock

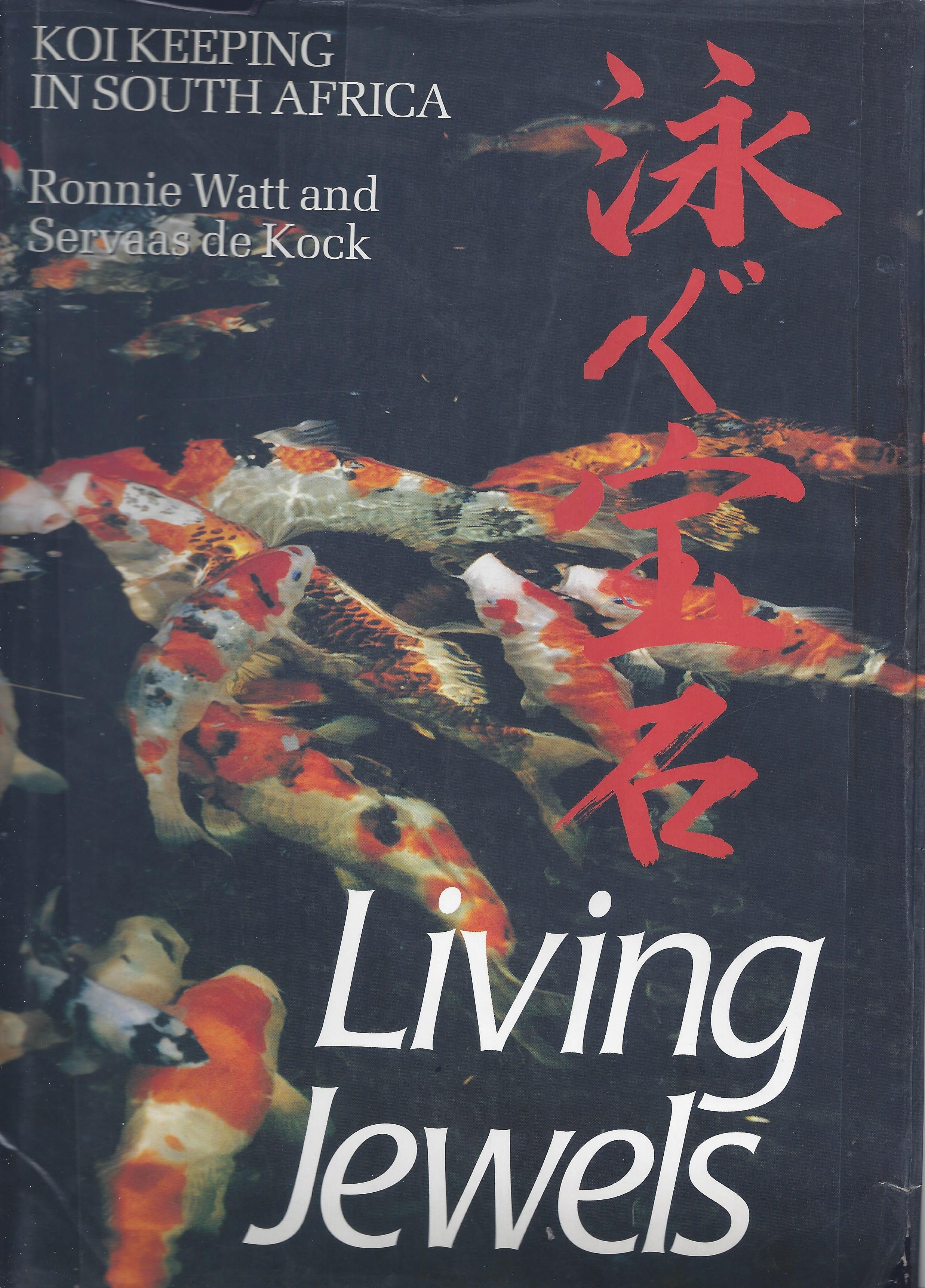

The copyright text is reproduced with permission from the authors from the book Living Jewels: Koi Keeping in South Africa, published by Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg, 2002

South Africa has every right to claim that it counts amongst the top koi-keeping countries in the world. Outside of Japan, Taiwan and Hong Kong, South Africa ranks equal to the United Kingdom and the United States of America in dedication to koi keeping and quality of koi collections. This is despite the fact that koi were introduced to South Africa only in the 1970s, whereas they were introduced to the USA in 1938, Hawaii in 1947, Canada in 1949 and Brazil in 1953.1 South Africa's status as a premier koi-keeping country is freely acknowledged by the many visitors from Japan and Taiwan who are leaders in their own and international koi keeper/breeder organisations.

The popularity of koi keeping in South Africa was researched in 1993 by Dr Neville Marais and Servaas de Kock, who found that 9,3% of all middle-income suburban households had a garden fish pond with a formal or informal collection of koi. The total investment in koi and the supportive infrastructure (for stock, food, medication, ponds, pumps, decorative features, etc) was estimated at R5,7 million, which represents an average investment of R20 800 per keeper, R129 500 per dealer and R54 200 per breeder. The average keeper was estimated to spend R1 729 per year on managing and improving the collection and the pond. The koi-perfect South African climate and South Africans' love of gracing their properties with attractive gardens contribute to a great extent to the promotion of koi keeping so far away from the traditional heartland of these fish.

Though the date of the exact introduction of koi into South Africa is vague, it is generally accepted that the early 1970s were the founding years. Alan Nementzik, as a school pupil in 1971, bought young koi off ships in Cape Town harbour. He recalls Japanese fishing ships reaching Cape Town harbour en route to the fishing grounds with goldfish and koi on board which the crews would sell for some extra pocket money. In those days the goldfish held a far greater attraction for the Cape Town dealers. Alan managed to buy some koi (mostly Kohaku) at five cents apiece and sometime later bred them in his swimming pool and sold the offspring to local pet shops. William (`Shorty') Bow of Rainbow Aquariums in Johannesburg started importing small koi in 1971. Terry Sole, who lived on the West Rand, got hooked on koi in 1972 and in the same year Chris Neaves of Randburg created a koi collection. Both Terry and Chris bought their first koi from pet shops in the Johannesburg area. Louis Fourie, who lived in Northcliff, Johannesburg, was the first known earnest importer of koi, obtaining his stock initially from Tamaki Farm in the Nagasaki Prefecture and afterwards from Nishikigoi Yoshida Co Ltd. Terry Sole also brought several boxes of koi into the country to be sold at cost to promote koi keeping. Barry Engelbrecht opened the first specialist koi dealership — first trading as Wonder Rock and then as The Plant Market — in 1982.

The earliest formal efforts at commercial breeding were those of the late Harold Court of Falls Fish Farm in the Eastern Transvaal, who was active by the mid-1970s. Amatikulu Fish Hatchery in Zululand, under the management of Fred Swart and Brian Andrews, released its first Ogon, Kohaku, Purachina and Sanke on the market in 1983. Mike Milani of Corriloch Koi Farm in Magaliesburg bred his first youngsters in 1988 and had his earliest successes with Shusui and Ogon. Like Amatikulu, the Corriloch parent stock were obtained out of Louis Fourie's Tamaki imports. Allan Stricke of Johannesburg, Willem Geldenhuys of Oudtshoorn, Manie Bouwer of Swartruggens and Dr Pierre Jordaan of Bloemfontein were actively breeding koi during the 1980s.

These dates and local histories pale against the interest in koi in the Far East. which spans many centuries. The word koi was first used about 2 500 years ago in China and Buddhist lore has it that a son of Confucius was given a fish named Koi by King Shoko of Ro at his birth in 533 BC. Shuji Fujita records it in slightly different detail, saying that Confucius christened his son Li (literally. Koi), probably because he wished his son to be as punctilious and orderly as the arrangement of scales on the koi's sides.' These early koi were carp which found their way probably from the Black, Azov, Caspian and Aral Seas via Persia and Korea to China. When the Chinese invaded Japan they took their fish with them.4 The first coloured carp are thought to have originated round about AD 250 with mentions in manuscripts of red, white and blue coloured carp to be found in Japan. Perhaps a more accurate review of the history of koi is that coloured carp originated in China between AD 700 and AD 1000 and were exported to Japan by the year AD 1500.

What is not disputed is that the 'modern era' of koi, with a more formal (even if haphazard at first) approach to breeding and refining of varieties can be set at AD 1800 when, in the region of Niigata Prefecture in Japan, where carp were bred as a food source, coloured mutations appeared. At first a red mutation was found (Hoo-kazuki), and from that, a white mutation. Cross-breeding of the two resulted in red and white koi (Hara-aka, meaning 'red belly'). These first Kohaku were in fact closer to the Asagi lineage than the purer (of later era) Kohaku lineage because the hi (the red) appeared on the abdomen (hara Hi) and reddish spots were to be seen on the gill covers (Hoaka). Further selective breeding in the region now known as Yamakoshi produced the Sarasa, a carp with a white body and red on its back and this must be taken as the true ancestor of the most prized of all koi, the Kohaku — a white-bodied carp with various patterns of red markings on its head, back and flanks.

The manipulation of genes to produce the Kohaku was completed in the Meiji era (1868-1911) when the Kohaku's red markings were successfully moved from the abdomen and cheeks (the classic hi pattern of the Asagi) towards the back and the top of the head (a classic pattern of the Kohaku).

Michugo Tamadachi, in his book The Cult of Koi, distinguishes further significant 'lines' of mutations. The first of these is the Bekko with variations of black markings on white, red and yellow. A significant event for cementing the foundation stock was the breeding of Sanke with its white ground and red and black markings.

Surprisingly, one of the principal lines of mutation strictly speaking did not have its genetic roots in Japan but rather in Germany where carp with either large reflective scales (mirror Doitsu) or no scales at all (leather Doitsu) were found. These carp were bred for their absence of scales because they were so much easier to clean for the frying pan!' Doitsu carp were first imported in 19048 by Japan to supplement the breeding of fish as a food source, but in crossbreeding with koi they produced beautiful variations on the traditional varieties.

Up to this stage the breeding of coloured carp as ornamental fish was restricted to the Niigata region. In 1914 the fish were introduced to a wider audience when Hikosabura Hirasawa, the mayor of Higashiyama Mura, sent 27 of them to the Tokyo Exhibition to elicit commercial interest that might help alleviate the economic poverty that held sway in Niigata. The collection of koi was impressive enough to be awarded the second prize for exhibits at the show and afterwards eight of them were presented to the son of the Japanese Emperor. This, it is said, launched the flourishing koi industry as it is known today.

One of the great genetic scoops was the breeding of the metallic variety — the Ogon: Tamadachi recounts that Sawata Aoki and his son found wild carp with golden scales on their backs and these were bred with great care to produce a wholly golden-scaled koi. This, according to tradition, happened in the first few years following World War II.

The Kinginrin line must also be mentioned for its contribution towards creating variety. Kinginrin (or Ginrin, as it is also known), meaning shiny scales, was first displayed at the first Yamakoshi Koi Show,1° though it was first seen and promoted by Eizaburo Hoshino in 1929.11 Kinginrin has been successfully introduced to virtually all of the present day varieties.

The dedication of many generations of Japanese koi farmers has given us the modern koi with its 15 specific varieties and a host of acceptable colour and pattern variations for each variety, some more sought after than others. The Ki Utsuri of the Utsurimono variety grouping was established between 1868 and 1912; Shusui was developed in 1910; the Sanke made its appearance in 1912 and the first Goshiki was recorded in 1918. Shiro Utsuri came into being in 1925; the Ai-goromo gained acceptance in 1940; Kujaku made their appearance in 1960 and Yamatonishiki and Midorigoi were bred in 1965.12 All of these varieties, their individual histories, their appeal and standards will be discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

New variations within varieties continue to be introduced, specifically within the Kawarimono grouping which, to the uninitiated, might seem a lumping together of 'the odd ones out'. Not all of these new Kawarimono variations are acceptable to the aesthetes — particularly if something like the `green' Midori (a cross-breeding of Shusui with Yamabuki Ogon) is mass-bred and dumped on the koi market in the West long before it has reached true status in the Far East. It is just as regrettable that koi which would be culled in the Far East, for example the black-masked 'hobos' out of Ogon and the all-white shiro muji out of Kohaku, are promoted as `keepable' and even `desirable' outside of the Far East — also in South Africa.

In the two decades spanning 1970 to 1990 South African koi keepers made rapid progress in acquiring the skills for proper pond management — they learned how to keep their collections alive! South African climatic conditions and available local technology did not always correspond with those of other more established koi keeping countries and the initial make-do was successfully developed into alternative koi keeping technology. Several innovative solutions were developed which would at times leave visitors from abroad dumbfounded if not green with envy.

In this period the quality of koi collections more often than not left much to be desired. The koi were generally of lower commercial grade, with only a handful of keepers able to display show quality fish. There was definite consumer resistance to the higher prices of imported koi — which must not be attributed to stinginess but rather to ignorance of what constitutes quality in koi. The appreciation of quality received its first boost with the founding of the South African Koi Keepers Society on 1 April 1988. Under the chairmanship of Terry Sole society members were exposed to several collections which featured excellent samples. As exposure to koi of this quality increased. motivation rose amongst members to achieve the same, and the small but regular imports of show quality koi by the likes of Terry Sole, James Norrie. Barry Engelbrecht and Chris Neaves were eagerly purchased.

The 1st National Koi Show of South Africa, which was held from 31 March to 1 April 1990 at the Rosebank Primary School in Johannesburg, attracted 290 entries. Apart from being a landmark event, it also served to encourage better quality collections because the cream of the South African koi crop was on display for comparison and to set a standard. By the time the 2nd National Koi Show was staged in the following year, koi keepers of the likes of Dr Tony Harrison were able to display top quality fish in the bigger sizes comparable to the best in any country outside the Far East. By 1992 the entries at the 3rd National Koi Show were sufficient proof that koi keeping in South Africa had stepped out of its baby shoes and was well on its way to earning international recognition.

Imports of koi from dealers in Japan and Taiwan fed the near-insatiable local demand for stock. A small number of enthusiasts managed to make direct buys of young bloodline-bred koi from breeders like Sakai, Jinbei, Dainichi and Hilasawa, and a few top grade fish bred by Dr Mao-Lin Tsai of Taiwan were also secured.

The koi boom had four specific drawbacks which impacted negatively on the average quality of South African koi keeping and on the ethics of koi keeping. As regards the quality of the koi, the first negative was that demand prompted mass breeding by inexperienced local breeders: inexperienced in the sense that non-bloodline parent stock was used and that the fry were released with little or no attempt at culling and grading. In the excitement of becoming 'breeders', the time-honoured and very sound guidelines of the Japanese master-breeders for breeding and culling were conveniently ignored. The 1991 membership list of the South African Koi Keepers Society gave 25 names of members who bred koi to some extent or other.

As a source of inferior koi in the country, the second culprit is Israel, where, in kibbutz style, commercial grade koi are bred to be sold to the koi-hungry markets of the USA, Europe and South Africa at such cheap prices that the buyers are blinded to their immediate and long-term inferior quality. At the height of the dealers' love affair with Israeli koi, thousands of young koi arrived at Johannesburg International Airport each week, the exports made easy for the Israeli marketers by government subsidy of the export air freight fees. It had disastrous effects on some of the more serious local koi breeders, who had to cut down on production and drop prices. The Israelis' impact on the world of koi is obvious from the boast by one of the Israeli marketers that his breeders managed to capture 22% of the cold water fish market in Britain as opposed to Singapore's 38% stake and Japan's 9% stake.

It was mentioned that the koi boom also had an adverse effect on the ethics of koi keeping. Koi keeping in South Africa gained much publicity during the early 1990s and much of this coverage focused on koi as a 'yuppie' investment opportunity. Financial magazines bandied about investment figures of up to R100 000 for a single koi whereas the truth is that at the time of writing, the most expensive single import was but R72 000 with less than a handful of others costing between R20 000 and R30 000. In a rather irresponsible way expectations were created that quick profits could be realised by investing in expensive koi and selling those koi within a year or two. The investors were never warned that, unlike for example gemstones, physical quality could degenerate under wrong management or that the intrinsic quality (aesthetic appreciation) could change and that the investments could turn out to be worth far less or even worthless.

The fourth drawback of the boom was that goldfish breeders saw greater profits lurking in koi and either switched from goldfish to koi or supplemented their goldfish breeding programme with koi breeding. None of the goldfish farmers had the vaguest notion of how to breed for quality and koi of the most inferior quality were therefore released onto the market.

If the cheap Israeli imports and the locally bred commercial grade koi must be given some credit, it is that they prompted greater interest in koi from the consumer base from whose ranks, eventually, came koi keepers converted to the quest for excellence.

South Africa's koi market eventually stabilised by 1993, when small-time profiteers were ousted from the market by the specialist dealers and the tide of favour turned against Israeli imports. Imports of quality stock from Taiwan and Japan resumed in earnest and at the same time a few dedicated — even if labelled small-time — local koi breeders started to produce show-winning koi. Dr Pierre Jordaan, Louis Marais, Dr Neville Marais and Willem Geldenhuys were amongst the pioneers in this field. A real breakthrough came at the 4th and 5th SAKKS National Koi Shows when Orient Fish Farm's own-bred youngsters snatched three Supreme Champion, one Tategoi and one Baby Grand Champion prizes. Such successes cemented the efforts by those full-time South African koi breeders who have dedicated themselves to producing higher quality koi.

Koi keepers in South Africa are no less than the junior but worthy ambassadors of the old koi breeding countries. In that sense we too are the guardians and promoters of the genetic treasure inherent in each and every koi.